The hierarchy of differentiation

Unsurprisingly, the content itself is the best way to differentiate a media brand

This is the eighth edition of The Rebooting. This week, I’m taking a look at how to differentiate as a media brand, assessing the Substack revolution, the game of putting too much mayo on the sandwich, and the power of resilience. If you’re enjoying The Rebooting, drop me an email -- and please forward this to someone who would find it valuable. Thanks for reading.

The hierarchy of differentiation

The past decade in media has been defined by commoditization. The shift from analog to digital distribution and monetization has been unkind to many publishers, none more so than those in the middle. All markets have middling players who struggle. The media business has seen even more pressure thanks to the rise of distribution chokepoints and data eating advertising. In a world of “find a cookie, hit a cookie,” content became a commodity. In a race to make up for declining ad rates, publishers adopted scale strategies that depended on serving the whims of algorithms. Inevitably these growth hacks became widely known and deployed. The result: A lot of sameness.

There is reason to be hopeful that we are entering a new era of publishing that will amount to a do-over for many of these ills. The promise of the internet has always been a low barrier to entry enabling unique people and brands to find passionate audiences and sustainable business models. That is more possible now through the combination of direct distribution, vertical focus and (often) direct monetization models. But the brands that can pull off DTC strategies need to be differentiated.

Community focus. The most powerful media brands are the center of communities. That can range from lifestyle to business verticals. Trying to be all things to all people is a mistake. Find a community.

Point of view. You don’t get to play a central role in a community without having a point of view. This is easy to see in politics, as the rise of partisan media shows clearly. But it’s just as true with brands like The Economist (free markets) or Barstool (bro life). Brands need to stand for something. Here’s how I described the editorial mission of Digiday in our “user manual” we gave to everyone joining the team:

Digiday is smart, honest and doesn’t take itself too seriously. We understand the mechanics and nitty-gritty of media and marketing, which allows our coverage of this tumultuous time to be honest and unflinching. We call a spade a shovel. We are not negative to be negative, but we believe that in this time of change there are issues that deserve attention. At the same time, we’re eager to highlight those making change happen in media and marketing. In all that we do, our goal is to give an honest portrait of what’s really happening in media and marketing in order to eventually create a healthy future for it.

Personality. The explosion of influencers and creators on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok has proven yet again the power of personality. The direct connection an audience feels to these stars is powerful. We’re seeing Substack and forward thinking publishers like Complex, Barstool and Axios capitalize on this dynamic. (The risk is obviously the limited enterprise value when it is tethered to a person.)

Packaging. Design is critical, but too much time and energy was devoted to packaging in the scale era. There was an idea that you could achieve differentiation by gussying up the content in a different way, whether through an app or a pivot to video. Now, it seems the path to differentiation is put content in an email newsletter and make all paragraphs bullet points with random words and sentences in bold. Packaging is important -- it helps in differentiating a brand -- but it can only get you so far. It serves a role in developing franchises -- this is why we focused on Confessions and WTF explainers -- but the packaging is less substantive than the actual content.

Tone. This is the weakest form of differentiation in my book. You often see tone as a differentiator used for youth-focused media brands. The Skimm got a lot of grief for its conversational tone that can induce cringes, at least with those over 30. Tone is important, but it can quickly become cliche. Anyone who regularly reads Axios is wearied by the constant “Be smart” exhortations. You can’t emoji your way to differentiation, particularly when lots of other people have figured out that an emoji in a subject line will goose open rates.

Mayo on the sandwich

When we were teenagers in the 1980s, we worked during summers. My friend Tom had a job at a boardwalk sandwich stand, serving up lunch to people on vacation without a lot of options. That lunch would be made by bored teenagers. That gave rise to a game Tom and his colleagues played: How much mayonnaise can you put on a sandwich before people complain? It turns out quite a lot, although eventually you do simply have so much mayo that the sandwich becomes indelible.

I’d use this story often in discussing how to balance revenue needs of a media business with having an audience-focused brand. In media, the game is usually to find just how much mayo you can put on the sandwich before it’s brought back as an atrocity. That’s why local news sites are mostly unusable. That’s why events are packed with sponsor sessions. That’s why publishers all privately grumble about Outbrain and Taboola even as they’re dependent on them.

The way out of this is simple but hard: Instead of thinking about how much mayo you can get away with, think about how much mayo would actually make the sandwich better. Consider aioli -- and be judicious about the amount. Ads aren’t bad, using data to make content (and ads) more relevant isn’t bad, sponsorship isn’t bad, mayo isn’t bad.

The Substack Revolution

Add Substack to the category of “things journalists are far more obsessed about than they should be.” CJR has an entry in the inevitable backlash to Substack, pointing out the very real limits of the Substack Revolution. That said, the momentum of Substack is real -- and I think has legs in remaking a part of the media ecosystem. Some key considerations:

Large paid newsletters are a niche phenomenon. There are few Ben Thompsons out there. The defection of big name journalists will continue to get attention, but a distribution curve will inevitably develop with a steep drop from the few who can achieve escape velocity.

Micro-media collectives have legs. The Dispatch and Defector are two publications benefiting from the trends Substack is both riding and spreading: direct distribution (newsletters mostly but also podcasts) and direct monetization (subscriptions). The opportunity to build small collectives under a single brand is larger than the solo Substack star. People like brands and bundles.

Subscription fatigue is real. There are only so many newsletters people will want to get -- and fewer still they’ll pay for. Substack is testing a way to bundle delivery of different newsletters, an important step in solving a critical need: discovery. Every platform has to do basic things for the businesses operating on the platform. Monetization is critical, but distribution is a close second.

Audience development is critical. Many Substacks are doomed to hit a wall at a relatively small number of subscribers. The reason I believe solo Substack warriors will be relatively few is I don’t see many journalists having the stomach for the marketing and audience development that’s needed -- and they don’t have the expertise.

News publishers will adapt. You’ll see new deals struck with “star” creators that enable them to have the benefits of media company infrastructure -- audience development, data strategy, sales, editing, tech -- with new economics that give the creator a share of the upside. You’ll see publishers adapt Substack-like strategies. I’m following what Morning Brew is doing with its new product recommendation newsletter, Sidekick, which is more tied to a person than other Brew newsletters.

The resilience factor

Over my time at Digiday, I hired 75 or so people into our group. As we grew, I didn’t directly hire each person but in nearly all cases I met with the candidates before we hired them. The textbook question I always got was what someone needed to do to succeed at Digiday. This is a tough one, since we had a lot of people succeed but some didn’t -- and the results didn’t always line up with what I’d have predicted on Day 1.

But the biggest indicator of a successful run was resilience. The pandemic has only magnified this as it stretches on. The reason resilience was so important on our team is most of the people were reporters. Reporting is hard. There is pressure to produce every day -- and from scratch. The work involves an inordinate amount of criticism. Editing itself is a form of criticism. And beyond that, Digiday has always been a rambunctious company that stretches itself to the breaking point. The people that accepted these realities and bounced back from setbacks tended to fare the best over the years. The good part about resilience is it can be learned, even though people weird like to make these kinds of traits out to be genetic. The challenge is building a culture that attracts resilient people but also builds resilience in people. Some ways:

Reward resilience. We started a weekly Perseverance Award at the start of the pandemic in order to recognize people for bouncing back and showing stick-to-it-ness. There is a tendency in many businesses to laud star performances vs consistency. Fight that.

Avoid ego. Confidence is great, but ego is deadly. There is a power in knowing what you don’t know. That kind of humility means someone is going to focus on improvement -- and on the process to improvement, which isn’t always pleasant.

Emphasize routine. We were big believers in habits. We had a standing huddle every morning at the same time; the all-group weekly meeting happened each week no matter what. Routine can seem boring, but habits enable people to focus on their work and growth. It instills a focus on the process vs just the results.

Final thought

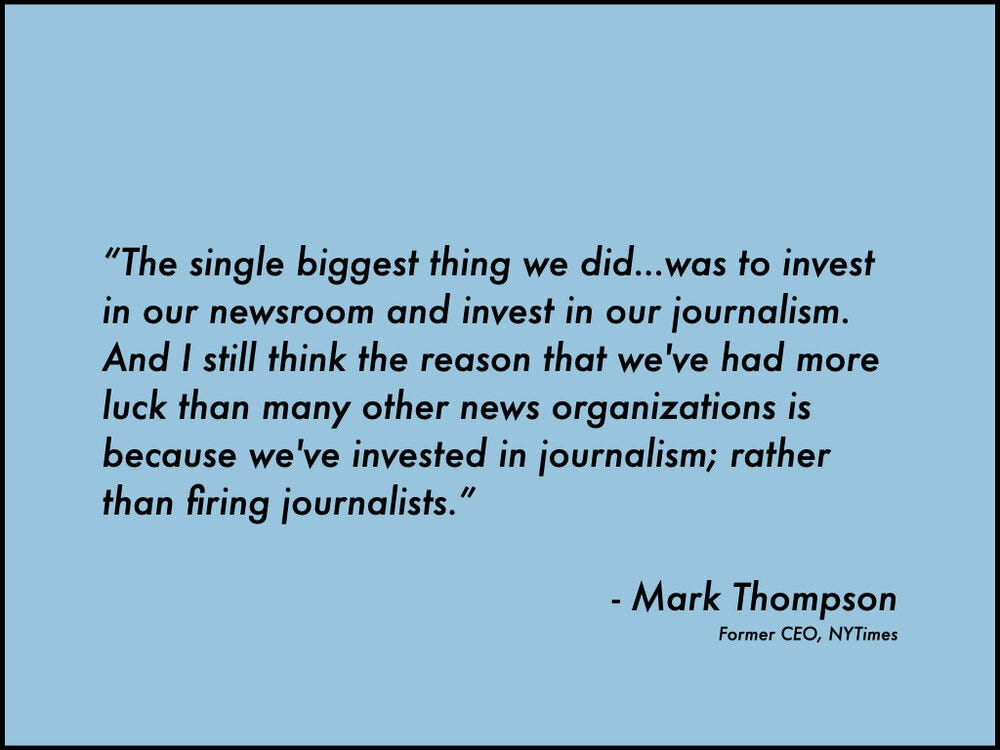

A Rebooting reader sent over this great presentation on the remarkable success story that is the business revival of The New York Times. The key slide that spoke to me was this: Sometimes people forget what is the core of the business and what drives the value creation.

Great stuff as always. I'd build slightly on the packaging one. Clearly the quality of the content is key, but we find that packaging is increasingly important to get people engaged with it - eg they'll engage far more with something repackaged into slide form than they will as straight text. It's a nuance, as you need the quality there in the first place. But I think it increasingly matters. Interested in your take.