The best way to make money

This week, I participated in my first Clubhouse. Punchbowl co-founder Jake Sherman made a great point: Substack is selling writers short with its no-ads-ever stance. As luck would have it, the continued need for diversified business models was my topic for the week. Also: a contribution from Jack Marshall on pricing subscriptions, and a case for taste as a moat.

Diversify

The excitement around newsletters and independent micro-media businesses is in many ways a do-over for the Web 2.0 era. The big difference: Web 2.0 was all about building large audiences through platforms that would be monetized with ads. Now, it’s about niche audiences and subscriptions.

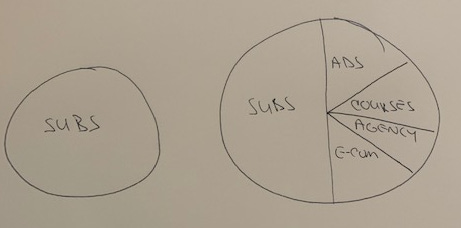

But that misses a big lesson of the blogging boom. As bloggers built businesses, they focused squarely, almost maniacally on ads. That made sense since, well, that’s what everyone was doing. That turned out, in most cases, the wrong bet. I’d argue, however, the big lesson was different. It’s that the best way to make money is: lots of ways.

Subscriptions beat ads for most media businesses for a few reasons.

You align your revenue with your product far cleaner than with advertising. As we have seen again with Robinhood, there are misplaced incentives when your users aren’t your customers.

You make fewer compromises with your product. Visiting an ad-dependent local newspaper site is like getting punched in the face. Not a way to keep an audience.

You start the year with money. Recurring revenue is the most powerful business model around. There’s a reason subscription software businesses fetch the multiples they do.

That said, subscriptions aren’t religion. Too often, people take absolutist approaches. (BuzzFeed was never going to run a display ad. Programmatic display is a big part of its business now.) Advertising is not an either-or proposition. The history of media says it’s usually an and situation. The businesses being created many independent newsletters will not be supported by a single revenue stream. Instead, they’re going to need several sources of revenue, including advertising.

To date, Substack has taken a no-ads-ever approach. I understand that -- from a marketing standpoint. Substack wants to position itself as an antidote to the doomscrolling of social media feeds. Substack co-founder Hamish McKenzie recently summed up the stance:

Substack is designed to be a calm space that encourages reflection. You read Substack posts in your inbox or on a web page that is free of advertising or any other distraction. There are no addiction-maximizing feeds, autoplaying videos, or retweetable quote-retweets to suck you into a psychological space you never asked to be in. You make decisions about which information to put into your brain based on how well certain writers reward your trust, not based on a dopamine hit gained by refreshing a feed packed with performative posturing.

And yet many Substack newsletters are already running advertising. More will do so. The dream of writing great content and relying solely on subscriptions will be available to a small group of stars. For Substack and micro media to gain traction, most will need a mix of revenue sources, including ads.

Pricing subscriptions

The most common question around subscriptions is simple: How much? Many will claim there is a science to pricing, but I’ve mostly found it a matter of looking at what competitors are charging. Jack Marshall, who built our memberships business at Digiday, offered his view:

Publishers should price subscription products based on the value, particularly if they’re aimed at business or “prosumer” audiences. Too often price points are arrived at using some combination of what competitors are charging, back-of-the-envelope math based on a 10% conversion rate and what Ben Thompson charges for Stratechery. Poor pricing risks undermining value, anchoring customers to unnecessarily low price points and lleaving money on the table. It's a particularly costly mistake for publishers catering to highly focused audiences with inherent scale limitations. Questions to consider include:

How easily can a customer justify the expense?

How big is the target market?

Are there competing products meeting the same needs?

How price sensitive is the target customer (or their expense account) likely to be?

Answers to those questions will differ for each publisher and product, which is why pricing should too.

Alternative media models

In journalism, three examples, even if slightly different, are sufficient for a trend. So we can call it a trend of a new wave of corporate media as companies realize that media is an often terrible business on its own but is an amazingly efficient marketing tool. Consider:

Penn Gaming bought a majority stake in Barstool a year ago. Since then, the company’s stock has quadrupled. Barstool has proven an ideal customer acquisition tool -- and Draftkings is probably kicking itself for not pulling the trigger on a deal.

Hubspot emerged as the buyer of The Hustle, a Morning Brew-like newsletter for those scratching the entrepreneurial itch. The deal is premised on the idea that “the next generation of software companies will invest in media that earns the attention of their audience.” The Hustle also brings a 1.5 million subscriber email list of potential customers.

Andreesen Horowitz caused tech journalists to clutch their pearls by announcing its own foray into publishing with an in-house organ.

Like everything in life and the world, none of this is particularly new. Media has long been the front end for many business models, from AARP to Glossier to Red Bull to Airbnb. That said, there is tremendous opportunity within niche media to align with subscription-based software companies. Many will attempt and fail to do this on their own. Usually, when companies attempt to “act like media companies,” they tend to produce PR or marketorial. Or they lose interest because media, especially niche media, is a long game.

Taste is a moat

A favored truism is money doesn’t buy taste. You only need to view photos of Mar-a-Lago to understand this clearly. Data and algorithms have become the be-all and end-all, often replacing taste. I remember the story of how at Google Marissa Mayer tested 41 shades of blue.

Testing won’t replace taste. “Saying that taste is just personal preference is a good way to prevent disputes,” Paul Graham notes. “The trouble is, it's not true. You feel this when you start to design things.”

Media is a frustrating business because there are few moats for it anymore. Owning a printing press and type-setting equipment, not to mention the distribution networks, was a good moat for a long time. Now, that’s gone. Media brands with particular taste can differentiate from potential substitution products. As Graham notes, taste is at the core of building products.

Within products, taste must be expressed consistently, in many different ways and by a diverse group of people. At Digiday, we would push for every aspects of products to have the same sensibility and taste. That meant site and newsletter design, but also our banner ads, sponsor content, events, podcasts and sales material. Taste won’t go away as a competitive advantage anytime soon.

Preparing for Long Covid

We are nearing the one-year mark of the pandemic. The New Normal is simply our abnormal lives. Early on in the crisis, the optimistic view was we could crush the virus like China and then enjoy a V-shaped recovery as economic fundamentals were strong pre-pandemic. Then, we settled on a K-shaped recovery as the rich got richer and the poor got poorer. Now, it’s time to prepare for Long Covid.

Long Covid is a mixed bag. Vaccine distribution continues to ramp up in the US while the latest wave of infections, hospitalizations and deaths decline. These are all positive developments. And yet the development of new variants, with evidence that some evade vaccines and spread more easily, means there are more twists to come. Life (and business) isn’t returning to normal anytime soon.

In-person events will not be the same for years to come. Testing, masking and other mitigation measures will be with us for years. Businesses will continue to scrutinize travel expenses. People are itching to socialize again. But the idea of Cannes Lions happening in June is hard to imagine. Large in-person events have a long road ahead. Hybrid events will rule the roost.

The old office isn’t coming back. Piling everyone into one place at the same time five days a week isn’t happening. The great remote work experiment has not been without its flaws, but the return of offices is likely to be a 2022 development -- and even then, businesses will look for smaller footprints and more flexibility. The upsides of offices -- communication, team building, efficient decision making -- will need to be adapted for a hybrid approach where people are dispersed for much of the time.

Things to check out

I was the guest on a couple podcasts. On The Coffee Podcast, I discussed the newsletter boom. At Interpublic Group’s Floor Nine podcast, we went over the outlook for Clubhouse and “social audio.”

Morning Brew has a new executive editor, Fortune’s Andrew Nusca. This is a key hire as it makes the pivot from its aggregation roots to include original reporting.

I’m speaking at a Newmark Journalism School event, Redefining Journalism Entrepreneurship, on Feb 19. The event is free and has some great speakers.

Axios took the wraps off AxiosHQ, its software product for companies to communicate more succinctly internally and externally. The track record of publishers selling software isn’t great, but Axios is addressing a real need here, as anyone who has experienced HR emails can attest. The key will be whether its services are up to snuff for big clients.